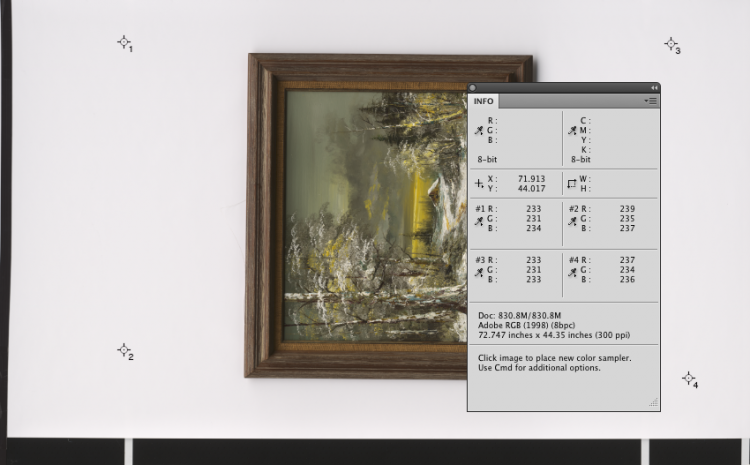

You can’t hardly run a tool like the Cruse Scanner and be limited to old-school ultra-wide printers or 44″ wide printing, now, can you? We think not. To keep the stable fresh, we just updated to the best ultra-wide possible. Introducing the latest and greatest in a 64″ wide printing machine- the Epson Stylus Pro 11880!

This printer has the remarkable Epson UltraChrome K3 with Vivid Magenta inks, the improved MicroPiezo® TFP print head, real-time automatic switching between Matte and Photo Black inks, automatic nozzle verification and cleaning, and more. In Epson’s words: “The result is the world’s most advanced 64-inch wide photographic printer”. We have to agree!

Combine that with our Angelica and Parrot ultra-wide media and it opens up a whole new world of printing capabilities- scanning and printing oversize paintings and artwork at life-size and bigger. Whether you’re an artist with huge originals, a gallery looking to produce editions at actual size, or even a commercial lab with 44″ printers and the occasional need for the width of the Stylus Pro 11880, give us a shout, or stop by and see the new baby. (info@parrotcolor.com)

Here, just for the drool factor, is the list of features from the Epson site:

Nine-Channel MicroPiezo TFP Print Head

- Print head design capable of handling nine separate ink channels

- One-inch wide high-performance print head with 360 nozzles per channel

- Low vibration meniscus control for highly accurate dot shape and placement

- All-new ink repelling coating to dramatically reduce nozzle clogging

Eight-Color Epson UltraChrome K3™ with Vivid Magenta Ink Technology

- High-density pigments for an extremely wide color gamut

- New formulation of Magenta pigments for extreme blues and purples

- Professional print permanence ratings for truly sellable quality prints

- High-gloss Microcrystal Encapsulation™ technology for reduced gloss differential

- Superior scratch resistance from improved pigment and resin chemistry

- Color is stable immediately after printing – no short-term color shifting

- Produces a black density up to 2.55 with an L* value of 2.9*

Epson AccuPhoto™ HD Screening Technology

- Advanced screening algorithm resulting in prints with superior color and clarity

- Maximum resolution of 2880 x 1440 dpi for incredibly sharp text and line art

- Extremely accurate fine blends and photographic transitions

Variable-Sized Droplet with TFP Technology

- Produces variable-sized droplets as small as 3.5 picoliters to greatly decrease print times while optimizing photographic quality

- Exotic Thin Film Piezo (TFP), along with Low Vibration Meniscus Control technology precisely controls the curvature of every ink droplet within each nozzle before releasing it onto the media. The result is extremely sharp and accurate placement of ink droplets for the ultimate in photographic print quality,

Advanced Black-and-White Printing Technology

- Unique driver technology takes full advantage of our three-level black system to produce professional black-and-white prints from color or grayscale image files

- Produces a truly consistent print with no color crossover or color cast

- Some of the world’s greatest black-and-white photography has been printed using this technology

Automatic Real-time Black Ink Mode Switching

- Printer utilizes two different black ink modes Photo Black or Matte Black

- This innovative solution optimizes black ink density for various media types, dramatically improving final print quality

Three-Level Black Ink Technology

- Simultaneously uses Black, Light Black, and Light Light Black inks

- Significantly improves the gray balance while eliminating colorcasts

- Outstanding highlight-to-shadow grayscale accuracy for a smoother tonal range

- Virtually eliminates any bronzing of the basic pigment chemistry

- Enhances the ICC profiling process for ColorSync™ and ICM™ workflows

Superior Connectivity

- Standard connectivity includes one USB 2.0 and one Gigabit Ethernet port

- Professional Epson Photographic Drivers for Macintosh® and Windows®

- Fully supported by most leading third party RIPs and workflows

Professional Media Handling with Automatic Roll Media Take-Up Reel

- Prints on virtually any media type, in roll or cut sheet, up to 64-inches wide

- All media is front-loaded via a unique straight-through media path

- Accurate automatic loading of cut sheet media up to 64-inches wide in a variety of weights up to 1.5mm thick posterboard

- User-adjustable Roll Media Spindle accepts either 2-inch or 3-inch media cores

- Produces impositions based upon a work-and-turn process, allowing for printing on both sides of certain media types

- Built-in Automatic Cutting System supporting most media types

- Standard Automatic Roll Media Take-up Reel for unattended production of long print runs

- Optional Retractable Fabric-Based Media Bin safely captures multiple prints up to 64″ x 36″

Automatic Media Bar Code Tracking and Identification System

- System automatically tracks media type, remaining length, media width, etc.

- Data is stored within the barcode and printed at the edge of the roll before unloading

- Reloading partially reused media rolls is now very efficient with less chance for mistakes

Epson Intelligent High-Capacity Ink System

- Pressurized ink cartridge technology ensures reliable ink delivery at all printer speeds, while dramatically reducing the physical size of the ink cartridges

- Nine individual 700ml (fill vol.) ink cartridges

- On-the-fly ink cartridge replacement for increased productivity

Unique Printer Activity Lighting System

- Nine individual amber LED lights provide live feedback about ink and printer activity

Automatic Head Alignment

- Built-in sensor reads printed data for highly precise alignments of all color channels

- Aligns both single and bi-directional print modes

Automatic Nozzle Verification and Cleaning

- Embedded sensors quickly verify nozzle status without using media

- System automatically performs a head cleaning if required

- Nozzle verification is performed in under 30 seconds

- Nozzle verification process consumes less than 1 ml of ink

- Can be set to automatically perform check before each job; periodically;

or can be turned off

True BorderFree™ Roll-Based Printing

- Capable of printing off both left and right edges of roll based media (up to 54″ wide), while automatically cutting top and bottom edges to produce a full-bleed print on all four sides

- Fully trims finished prints more accurately and safely than by hand

High Performance Print Engine Speeds

| Print Mode | 16″ x 20″ | 20″ x 30″ | 40″ x 60″ |

| Normal – 360 dpi HS | 0:50 | 1:24 | 4:08 |

| Fine – 720 dpi HS | 3:09 | 6:19 | 19:45 |

| SuperFine – 1440 dpi HS | 4:42 | 8:17 | 25:52 |

| SuperPhoto – 2880 dpi HS | 7:39 | 13:24 | 42:10 |

* HS = High-Speed Print Mode (Bi-directional Print Mode) | Print speeds are shown in min:sec

Based upon print engine speed only. Total throughput times depend upon front-end driver, RIP, file size, printer resolution, ink coverage, networking, etc.

Epson PreciseColor™ Manufacturing

- Unique production technology to ensure printer-to-printer color consistency

- Colorimetric calibration is performed during the manufacturing process

- This process automatically evaluates and adjusts the color performance of each printer

- The result is extreme color repeatability for demanding color performance over time

- Completely eliminates the need for internal printer calibration devices or procedures